What is Senile Osteoporosis?

Causes and Symptoms | Complications |Treatment |Final Words

Your 70th Birthday Means Cake, Candles and a Big Warning!

For every birthday we celebrate, we hope for a few rewards. Presents from family and friends, cake and candles, and a flood of great memories highlight the day.

But your 70th birthday is also a BIG WARNING about a condition called “senile osteoporosis.”

(Now, before you freak out about that word, this has nothing to do with senility, dementia, or Alzheimer’s disease. Senile osteoporosis is one of two types of bone density problems identified by the medical community.)

Today, we’re going to discuss the definition of senile osteoporosis, look at some senile osteoporosis treatment ideas, and hopefully answer a few questions such as, “What is senile osteoporosis, what are the complications and what are the treatments?”

So, let’s start with a quick definition of the different types.

Two Types of Osteoporosis:

- Type I osteoporosis (postmenopausal osteoporosis) generally develops after menopause, when estrogen levels drop precipitously. These changes lead to bone loss, usually in the trabecular (spongy) bone inside the hard cortical bone.

- Type II osteoporosis (senile osteoporosis) typically happens after age 70 and involves a thinning of both the trabecular (spongy) and cortical (hard) bone.

Causes and Symptoms

The main features of Type II are the loss of the body’s ability to make vitamin D and the failure of the body to absorb calcium, which leads to the loss of both hard and spongy bone.

Typically diagnosed through a bone density scan, one way to approach this form of osteoporosis is to supplement with vitamin D and calcium. (Your chances of developing this type of osteoporosis decrease by not smoking, restricting the use of alcohol, and by getting regular exercise.)

As we age, and most typically after 70 years, your kidneys become impaired and absorption decreases and your ability to make vitamin D also follows. The reduced concentration of vitamin D in the body restricts the amount of calcium that can be taken up. Low calcium levels cause the parathyroid hormone to signal the body to reabsorb bone to compensate for the calcium deficiency. The result is the gradual eroding of the hard and spongy bone, increasing the risks of bone fractures.

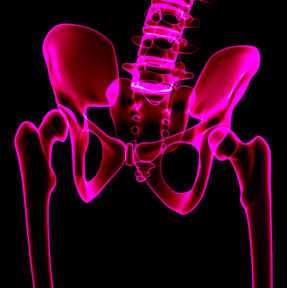

Sadly, it is only after the fracture of a bone (hip, back or wrist, usually) that many medical professionals make the diagnosis of Type II osteoporosis. When your doctor knows if your family history includes senile osteoporosis, he or she may order yearly bone density scans to track bone loss. Ultrasounds or quantitative computerized tomography scans can also identify depleted bone density.

Complications of Senile Osteoporosis

Several medical journals and studies list the complications of Type II osteoporosis, and they include:

☑ Vertebrae fracture – Fractures of the bones in the back.

Only about one third of vertebral fractures are actually diagnosed, because many patients and their families regard back pain symptoms as “arthritis” or a normal part of aging.

But if left undiagnosed and untreated, vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) can lead to long-term complications, including progressive kyphosis (curvature of the spine) and height loss, debilitating pain, and increasing deficits in physical, psychological, and/or social functioning. This is known as the “downward spiral.”

Complications include:

- Reduced range of motion and prolonged inactivity

- Respiratory decrease and increased lung disorders, such as a collapsed lung or pneumonia

- Decreased appetite and poor nutrition due to compression of abdominal organs

- Constipation

- Bowel obstruction

- Deep venous thrombosis

- Progressive muscle weakness

- Loss of independence

- Crowding of internal organs

- Higher risk of future VCFs because spinal misalignment can shift a patient’s center of balance

- Increased mortality

☑ Colles fracture – Wrist Fracture

Patients with Colles’ fractures have serious complications more frequently than is generally appreciated.

A study of 565 fractures revealed 177 (31%) presented complications such as persistent neuropathies of nerves in the arm (forty-five cases), radiocarpal or radio-ulnar arthrosis (thirty-seven cases), and malposition-malunion (thirty cases). Other complications included tendon ruptures (seven), unrecognized associated injuries (twelve), finger stiffness (nine cases), and shoulder-hand syndrome (twenty cases.).(1)

☑ Hip fracture

A hip fracture can reduce your future independence and sometimes even shorten your life!

About 50% of people who have a hip fracture aren’t able to regain their ability to live independently. If a hip fracture keeps you immobile for a long time, the complications can include:

- Blood clots in your legs or lungs

- Bedsores

- Urinary tract infection

- Pneumonia

- Further loss of muscle mass, increasing your risk of falls and injury

Additionally, people who’ve had a hip fracture are at increased risk of weakened bones and further falls — which means a significantly higher risk of having another hip fracture.

☑ Death due to post-fracture complications(2)

Hip and vertebral fragility fractures are associated with significantly increased mortality rates.

No single factor predicts excess risk of death, and no proven solution to improving fracture survival in osteoporosis in all populations has been identified.

The independent role of fractures versus other factors, including functional status, comorbidities, capacity for independent living, etc., in increased mortality rates is uncertain.

Aggressive treatment of osteoporosis, especially in patients who already suffered from a fracture, reduces morbidity and may translate into longer-term survival. Future research should help to better characterize critical predictors of mortality and to design cost-effective interventions with the goal to reduce short- and long-term morbidity and mortality in patients at greatest risk.

Senile Osteoporosis Treatment

While there are several chemically-based (prescription) drug options, plus the use of estrogen replacement therapy to combat the effects of senile osteoporosis, the best treatment options begin with prevention.

Now, while it is too late to turn back the hands of time and knock a few years off your birthday, more reasonable areas to focus on are all-natural, organic solutions.

Leading the way is calcium. You have two basic options to increase your calcium intake: rock-based and plant-based calcium. And no one really wants to eat rocks, right? So, your best option is a plant-based source of natural calcium.

The second key ingredient you should include in your regime is Vitamin D.

Vitamin D is considered to be necessary in the therapy of senile osteoporosis due to the reduced kidney function found in the elderly. Small doses of vitamin D are considered to be the most efficient in continuous daily therapy.

But that’s not all. Your bones need more than just calcium or vitamin D. They need vitamin K2, magnesium, boron and trace minerals. For more on how to get this, go here.

A Few Final Words about Senile Osteoporosis…

Fractures in elderly persons are of an epidemic character.

As years go by, the number of fractures is increasing, which has a great socio-economic and medical importance. Significant financial resources go for the prevention of these fractures. Trauma, especially the trauma of the spine and hip fractures, worsens and makes basic diseases in elderly people more acute, the consequence of which is a high percentage of mortality.

The main cause of fracture in elderly people is osteoporosis. The number of fractures in elderly people can significantly be reduced by proper treatment of osteoporosis.

To make sure you get the very best bone building and bone repair supplement, check out this opportunity!

Sources:

- Cooney WP 3rd, Dobyns JH, Linscheid RL. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(4):613-9.

- ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4124750

- facta.junis.ni.ac.rs/mab/mab200501/mab200501-03.pdf

Pilar Portaro

April 16, 2016 , 10:09 amHello, I take Algaecal Plus everyday. I would like my husband, who is 68 years old to take it too. My question to you is if he can take it safely having had one of his kidneys removed due to adenocarcinoma of clear cells. Please, dont suggest that we ask his doctor about it, because very few in Peru know about your product. Thanks. Pilar Portaro